Becoming a more resonant body

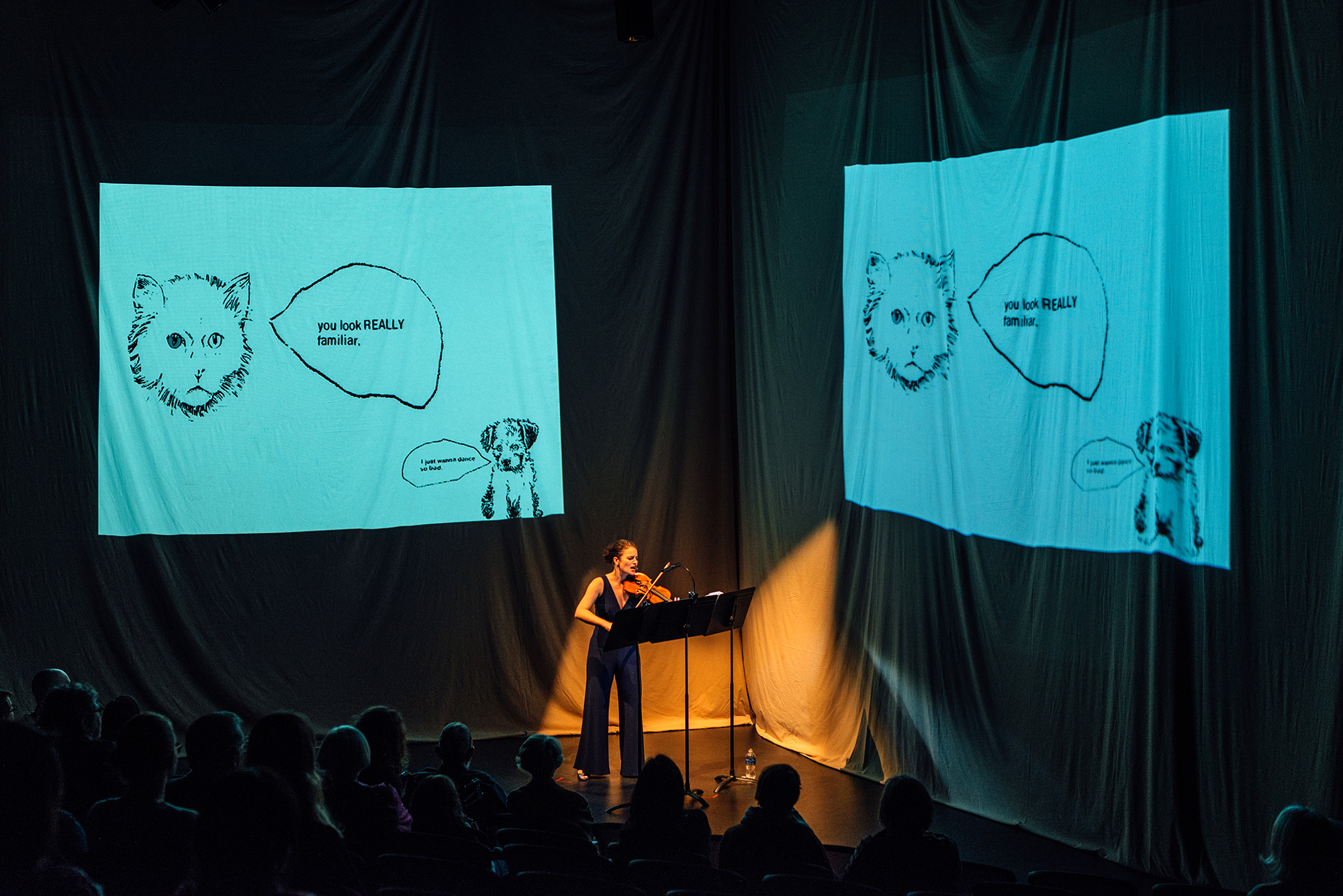

Performing Rodney LIster's "Explanatory Notes: The Only Difference Between" at the Lied Center in Lincoln, NE. Photo credit: Rana Young

There is a lot of singing in my family. Not just singing in church and school choirs but extensive Gilbert and Sullivan, Amahl and the Night Visitors type of sing-alongs over extended family gatherings. When I was a kid my father sang in opera productions in summers off, and both sets of grandparents revered vocal expression. Perhaps it’s not surprising that my sister Abby Fischer became a professional singer. What began as her almost constant humming as a child (sometimes to her family’s annoyance) transformed into a gorgeous, heart-rending mezzo-soprano voice that still brings me to tears every time I hear her.

Abby’s trajectory (and that of all singers) fascinates me. The way a beautiful voice grows and deepens with age and experience is different from the way an instrumentalist develops; we instrumentalists traditionally seek resonance from our instruments while vocalists find resonance from within their bodies. My sister recently sang in the 2016 Resonant Bodies Festival in New York, a festival devoted to programming stunning vocalists in cutting edge new repertoire and configurations. Just looking at the programs provoked the questions: what IS a resonant body and how do we make sound?

I have been thinking about these questions of resonance quite a lot recently while exploring the range of my own voice. For my 40th birthday last winter, my husband presented me with a ridiculously marvelous gift: solo violin commissions from eight composers (and a premiere date for August 2016)! While this was a surprise in and of itself, two of the pieces were written for “singing violinist” and one for violin and vocalizations. Byron Au Yong’s music (composer of “Water Partitas” for violin and vocalizations) was entirely new to me and I loved it immediately. The two composers who wrote for singing violinist, Lisa Bielawa and Rodney Lister, are people whose work I had performed in previous years, and I couldn’t wait to get started.

In 2012 my sister Abby introduced me to Lisa Bielawa’s “Kafka Songs.” These haunting songs are set to texts of Kafka and were written for Carla Kilhstedt, an inspiring musician I met as a teenager in Oberlin, Ohio where we both studied with violinist Kathleen Winkler. I had been looking for a challenging solo project, and Abby said, “well, I’m sure you’ll figure it out, go for it!” (My last great vocal triumph had been as a laryngitis-ridden donkey in “The Christmas Jazz” in 1986, so it had been a while since I thought about solo vocal performance.) The idea of singing and playing together was exciting to me, if slightly terrifying, so I learned four of Lisa’s songs and performed them in 2013. At that time I was mesmerized by Lisa’s music and loved the challenge, but I don’t think I was fully owning the vocal aspect.

This time around, however, instead of focusing on the novelty I wanted to explore the deepening of my own resonance. That would mean practicing the vocal part a lot, taking some voice lessons, and learning to love the sound of my own voice, something I found to be quite difficult. It was easy to make excuses—“I’m not really a singer, but I’m doing these pieces…I mean, I’m primarily a violinist, well only a violinist, but I’m working on these pieces, etc”—but that attitude only prevented me from enjoying my voice, however small or wobbly it was at the moment. And aren’t we all singers in some respect?

The voice lessons I had with my sister were incredible. She was patient and kind, and she helped me to ground myself and sing from my heart. She also stressed the importance of having a character motivation for every single word and phrase I sing or speak. It occurred to me that although it’s never ideal, one can often “get away” with a mildly boring violin performance the goals of which are things like good intonation and consistent bow technique. But when there are words involved, one has to make their meaning the focus: purely technically-oriented vocal performances are flat and meaningless. So for Rodney Lister’s piece “Explanatory Notes: The Only Difference Between” which switches between singing and speaking and involves many character changes, I carefully wrote in my chosen characters beside each line of text: 1. sassy friend, or 2. urgent truth, or 3. judgmental Republican grandmother (JRG), etc. This helped me to make sense of the text and sell the music more convincingly while also inspiring me to think of all of my performing in these terms, regardless of whether or not the music has words.

Acting as a singing violinist is at the best times an arrangement of true intimacy. It is an unusual opportunity to dialogue with myself—also the topic of Lisa’s astonishing, soul-searching piece “One Atom of Faith,” set to a poem by Mary MacLane—a time to accompany myself from both angles. I have great admiration for the singer-songwriters and performers who experience this type of collaborative relationship everyday as pianists, string players, guitarists, percussionists. And with each performance of these birthday commissions I will keep searching for ways to become a more resonant body.

From a live performance September 25, 2016, five of Byron Au Yong's "Water Partitas" (video by Anthony Hawley of The Afield):

For more information about the solo violin commissions and performances, visit: www.theafield.com.