Color, water, sound at Aster Montessori School: wonder in the everyday

Painting with colored sea ice

What is it about a fresh ice cube that makes us eager to touch it? Or the satisfying feeling of plunging a paint brush into a new set of watercolor paints? The inviting sound of someone’s voice that compels us to join singing?

The Afield, Anthony Hawley's and my collaboration, spent a week as Artists-in-Residence at the beautiful and forward-thinking Aster Montessori School in Cambridge, MA, investigating these universal impulses. Our program through four visits to Aster during the 2017-18 academic year is entitled Water Partitas, based on Byron Au Yong’s eponymous pieces written for me in 2016. Through the Water Partitas Program we will guide young children to interact with water, color, and sound in the children’s familiar environments, eventually helping them to create musical scores for all of us to perform in their community.

For those not familiar with the Montessori philosophy, Dr. Maria Montessori was an Italian 20th century educational pioneer. She developed a way of learning that puts emphasis on children’s autonomy through giving them tools to make their own choices about their activities and sharing the work of a participatory community. All of the materials in the classroom are called "works" and can consist of, at least in a young children's community ages 3-6, various things like tracing metal inset shapes to continent puzzle maps to washing a table. Each work has a specific purpose, and it is up to the child how long they will spend on any given work. The focus on process and choice in a Montessori classroom is a beautiful thing to witness.

Anthony and I were both fortunate to attend Montessori schools when we were young, and our own children attended an idyllic Montessori school on a Nebraska farm called Prairie Hill Learning Center. It was here that our girls grew a love for the outdoors and responsibility for self-care starting at the young age of 1 1/2. We also learned a great deal about how to be patient parents.

With these experiences in mind, Anthony and I heard about the Wildflower Schools, a network of Montessori schools in Cambridge and other Massachusetts and Minnesota communities. Founded by a former professor at MIT Media Labs, these are small schools designed to pop-up (like wildflowers) in storefront locations. The network keeps schools small—only two main teachers per school who are also the administrators—for hands-on learning and integral family participation. We were immediately drawn to the network’s key principles that include having an Artist-in-Residence program within the schools. As artists embedded in a community, we can share our work with children in the classroom by designing work stations and stimulating their curiosity just by doing our daily work routine.

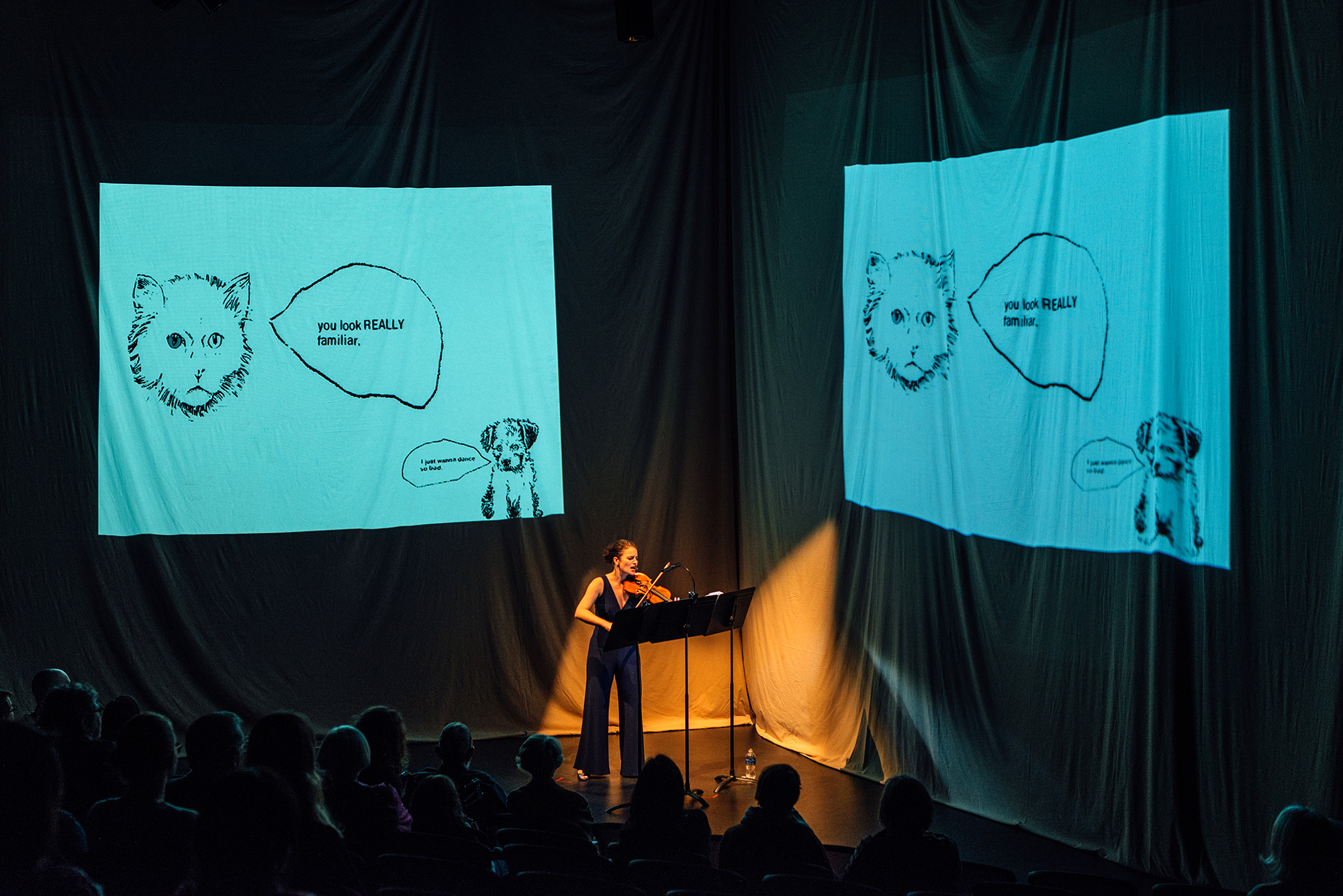

Mid-October marked our first visit to Aster, focused on introducing our work as The Afield to the children through presentation of our materials. We began with a performance for the 15 children and later for their parents and siblings of a few short works by J.S. Bach, Byron Au Yong, Nico Muhly, and Paola Prestini, in addition to some of our own original work for violin, voice, and video.

The week progressed with the introduction of work stations involving water drawings, water videos with accompanying sounds, glass singing, colored ice-making with both tap and sea waters, and vocal improvisation with video. Some of the most empowering work from my perspective was improvising while a child painted—we each gave the other cues. As adults we tend to question every little choice (from both the visual and sonic sides) to the point of paralysis. But when 3-5 year-old children draw with freedom it is a wondrous thing to behold, and seeing them smile as I accompany their drawing with violin improvisation is thrilling.

Aster's morning circle

I was similarly awed and reminded by the power of simple questions to elicit artistic awareness. For example, watching a slow-moving video of a sea star is already a pretty awesome experience for a 5 year-old. If you ask that same child to make a sound for the sea star, they will do so with delight. Other children will contribute different sounds, and suddenly we find ourselves with plentiful artistic choices. Likewise, figuring out multiple ways how to melt colored ice for art-making is an example of a practical decision moved into the realm of art.

Interestingly, there were a few well-thought-out works that didn’t engage the children in ways I would have thought; on the other hand, there were times when an activity I considered mundane was fascinating for the children. One example was when I put on a violin mute because I didn’t want to play too loudly while some children were resting. Other children flocked around my violin case and started asking questions about the sparkles on my mute as well as the sound. I demonstrated the way the violin was muted with the “sparkly” rubber mute, but then took out all of the other mutes I have—leather, aluminum, wood—and we had a fun time listening to the multiple possibilities created with these options.

As Anthony and I continue to develop our plans for The Afield School (our dream to open an interdisciplinary performance art space from where we also offer classes, also in a mobile, pop-up platform), it is important to us that we choose thoughtful and rigorous institutional partners. Thinking of a young children’s community as “rigorous” may sound odd to some, however in terms of the way that the Montessori method creates an environment for openness as well as structure for children, partnering with Aster Montessori School makes so much sense for us. At the young age of 3, children are all eager to explore and experience wonder about the world in an inspiring way. I feel fortunate to be involved in some of these children’s first experiences with the world as an artistic playground.

Exploring the singing of wine glasses